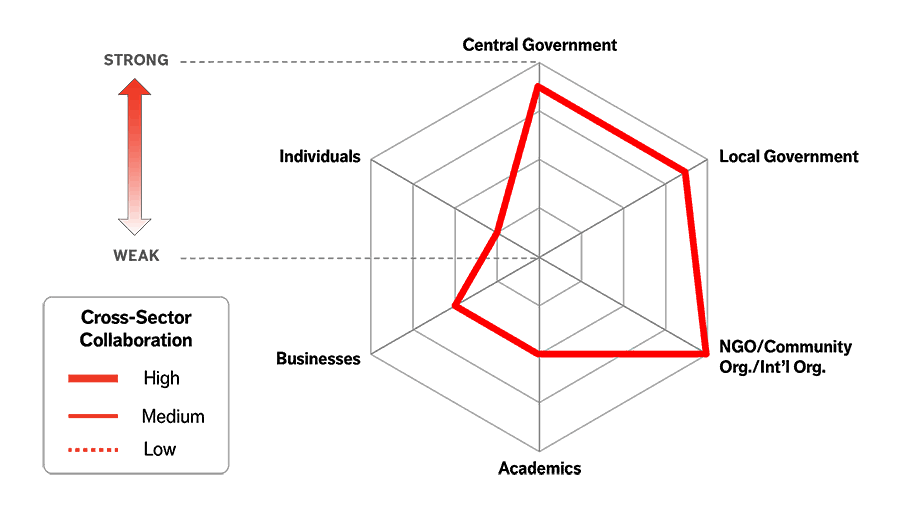

Ecosystem for Policy and Social Innovation

Aging-related policy and social innovation in Australia are characterized by strong grassroots and state-level engagement, as well as a person-centered approach. Underlying these attributes are the country’s tradition of civic engagement and its consultative and evidence-based approaches to policymaking. While coordinated actions between the federal and state governments help facilitate policy implementation, a weak political appetite for the top-down approach could undermine the country’s ability to create coherent national solutions.

“Sometimes the government simply doesn’t have that type of intelligence in house, and by going out and asking for information or insights from relevant stakeholders, its ability to develop policy is strengthened.”

– Kirsty Carr, National Policy and Strategy Advisor at Dementia Australia

Driving Forces of Innovation and Cross-Sector Collaboration

Community Social Infrastructure

Older adults in Australia tend to live happy, independent lives, with higher levels of reported life satisfaction than the general population. This can be attributed to their access to, and participation in, various social activities, including a national network of intergenerational playgroups that promote cross-generational communication. The growing movement to build age-friendly communities around the country, mainly driven by city and state governments, promises to further improve the well-being of older adults.

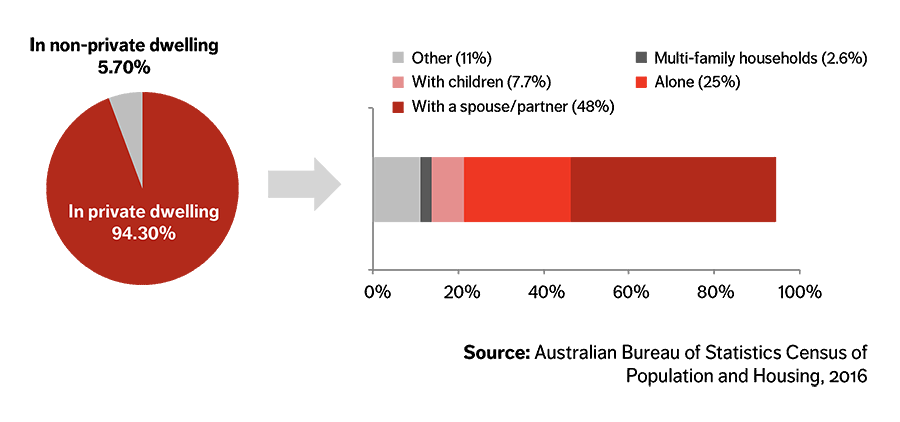

Living Arrangements of People Age 65 and Older, as of 2016

Intergenerational Playgroups

An interesting model, known as intergenerational playgroup, has been widely adopted to enhance cross-generational ties. The model evolved from the long-lasting, widespread practices of playgroups, which first emerged in the 1960s in Australia, and were originally designed to facilitate community-based support for early childhood development. Today, there are thousands of playgroups across the country, and each of the six states has a non-profit playgroup organization working separately to support local playgroups and coordinate with the government.

An intergenerational playgroup usually involves at least three or more generations participating. Specific practices vary, and one prominent model is intergenerational playgroups offered at long-term care institutions. First piloted in the state of Western Australia in the early 2000s, it was later replicated in other states including Victoria and Western Australia. Typically, parents and their children, including babies, meet weekly with older adults living in care institutions, spending a couple of hours together singing, painting, and telling stories. The institution’s staff is trained to facilitate the sessions.

“The practice has shown a positive impact on older adults’ social well-being and children’s cognitive development. In particular, it moves away from the traditional nursing home’s approach of solely ‘reflecting on the past’; instead, it promotes older adults to find purpose at the present in connecting with children.”

– Carley Jones, Executive Officer of Playgroup SA

Productive Opportunity

Older adults have steadily increased their productive engagement in Australia since the early 2000s, widely attributed to both demand for labor and a series of government initiatives tackling barriers for both employers and employees. Nevertheless, older adults’ labor force participation rate is still below the OECD average, indicating room for further improvement. Senior entrepreneurship is one promising area.

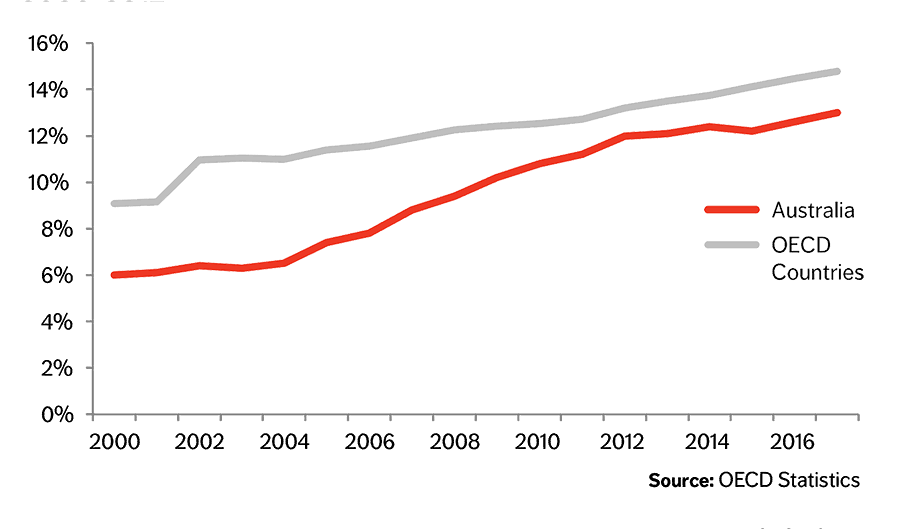

Labor Force Participation of People Age 65 and Older, 2000-2017

As of 2017, the labor force participation (LFP) of adults age 65 and older was 13 percent, more than double the level in 2000. While still below the OECD average at 14.8 percent, the gap is shrinking.

(Source: OECD)

Combating Ageism

Realizing ageism has an economic cost, the Australian government is seeking to combat ageism in the workplace. It is estimated that Australia loses over AUD 10 billion (USD 7.2 billion) per year as a result of people staying unemployed due to age discrimination. In 2004, the government passed the Age Discrimination Act (ADA), stipulating that it is unlawful to treat people unfairly on the basis of their age. To enforce the Act, the Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC), a statutory body funded by the government, is responsible for receiving and conciliating complaints; those that are not resolved are taken to court. However, the difficulty in proving a discrimination complaint is a key impediment to the ADA’s effectiveness.

To both understand the scale and scope of the challenge and to be able to measure progress going forward, in 2014, the government conducted the first National Prevalence Survey of Age Discrimination in the Workplace. The report, which was released in 2015, quantified the prevalence of workplace age discrimination of people age 50 and older, and identified its nature and impact. The government intends to use the survey results as the benchmark against which it can judge the effectiveness of anti-ageism programs going forward.

Technological Engagement

With its low population density and continental scale, information and communications technology (ICT) has the tremendous potential to enhance the well-being of older adults. Australia has invested in a world-class ICT infrastructure, ranking among the top 20 countries on the World Economic Forum’s 2016 Networked Readiness Index. As such, it is well positioned to harness the power of digital technology to accommodate its aging population. The government has focused on enhancing digital inclusion, including the rolling out of a national digital literacy initiative for older adults in 2017. The growing market of older consumers has also begun to draw interest from the private sector, but there is limited policy support for the development of technology solutions for this demographic.

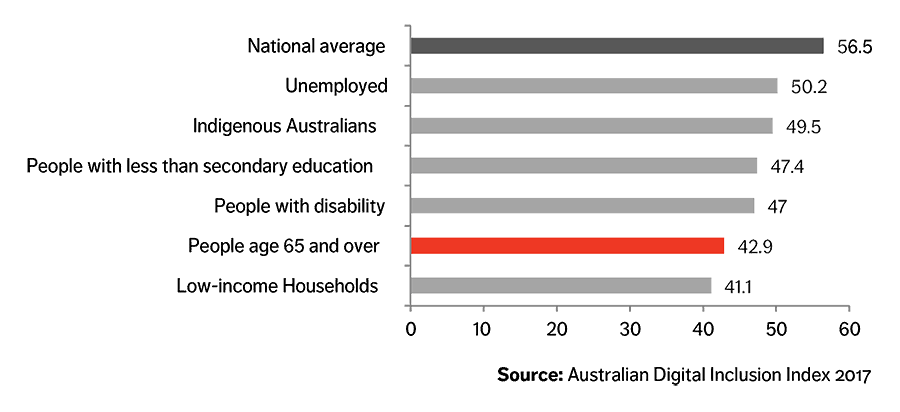

Digital Inclusion Score, 2017

“Introducing technologies, face to face, is the best way to engage this audience; it’s also important to make sure the education material is culturally appropriate and delivered by a trusted individual from within the community.”

– Mark Sulikowski, Senior Advisor of Indigenous Digital Capability at Telstra

Be Connected Initiative

The most recent push by the Australian government to promote digital inclusion is the Be Connected initiative, launched in October 2017. Be Connected replaced a national program known as Broadband for Seniors, which deployed internet kiosks at community organizations to facilitate access to the internet and training programs. The new initiative continues to leverage existing community infrastructure and expertise, but also focuses on empowering the broader community to play an important role in promoting the adoption of digital technology. To this end, the initiative provides both online and offline support:

- A dedicated website that provides training tools, materials, and other useful information for older adults, their families and friends, and local community organizations.

- Offline access to free one-on-one coaching for people age 50 and older, provided through a national network of community organizations, including libraries, neighborhood centers, community clubs, and retirement villages, among others.

The government provides funding and capacity-building support to participating organizations, targeting a total of 2,000 organizations that provide personalized training for up to 100,000 older adults per year. While still too early to gauge the success of this initiative, more than half of those age 50 and older who were surveyed in 2017 expressed interest in participating.

Health Care and Wellness

Already home to one of the world’s healthiest older populations, Australia still grapples with how to the respond to the rise of chronic diseases and demand for long-term care (LTC). The government has responded with a focus on enabling older adults to have access to integrated care. This person-centered approach is also adopted in the government’s recent reforms in the LTC system, as it aims to provide consumer-directed care and enhance older adults’ choices of providers.

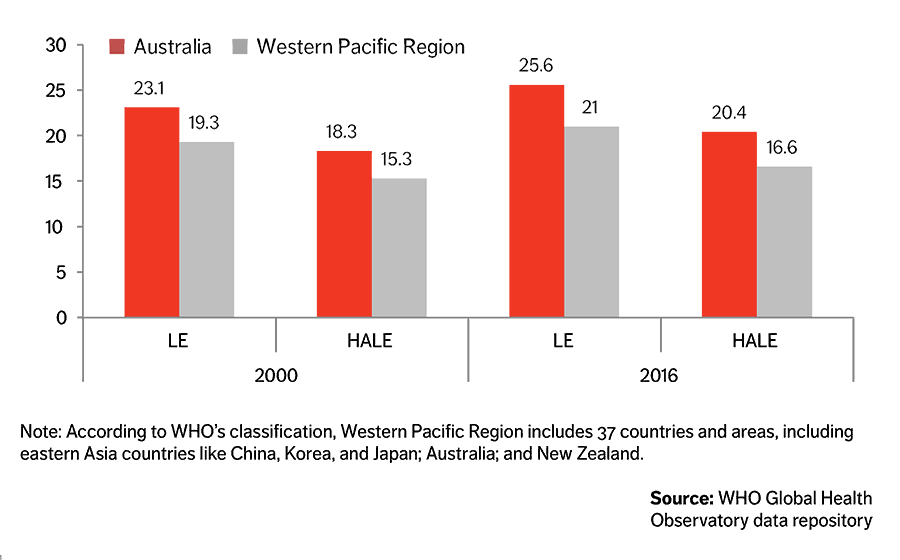

Life Expectancy (LE) and Healthy Life Expectancy (HALE)

at age 60, 2000 vs. 2016, in Years

As of 2016, an average adult at 60 was expected to live another 25.6 years—the fourth highest in the world (after Japan, France, and Canada); the average healthspan was 20.4 years, fifth globally (after Singapore, Japan, France, and Canada).

Source: WHO Global Health Observatory data repository

Health Care Home

In 2017, the government introduced a National Strategic Framework for Chronic Conditions, built on consultations with a broad spectrum of stakeholders. The Framework emphasizes a shift from a disease-specific approach to a systematic, person-centered approach and promotes coordinated care across the health sector. Aligned with this emphasis, one model the government started to experiment with in 2017 is a Health Care Home (HCH). In an HCH, eligible individuals enroll with a participating general practitioner (GP), who will coordinate all their chronic disease management and facilitate their access to integrated care tailored to their needs. GPs will receive a bundled payment between AUD 591 and 1,795 (USD 425-1,291) per year, based on their assessment of a patient’s needs. Together with the patient, the GP will develop a care plan, including:

- Compiling comprehensive information about the patient’s health, medications, and all the health professionals who care for them;

- Identifying local health care providers that are best able to meet the patient’s needs, and helping coordinate care with these providers;

- Developing strategies to help the patient to manage their chronic conditions in daily life.

The HCH model is currently in trials in 10 selected primary health network regions, and more than 170 general practices (including medical centers, clinics, and other general practice providers) have participated. The trial phase will run through November 2019, at which time it will be evaluated to determine the impact of the new approach on patients’ health, hospitalization, and costs.